May 03, 2016 12:49 AM

When journalists and media rights activists gather in Helsinki to

mark World Press Freedom day Tuesday, there will be a notable absence:

Journalist Khadija Ismayilova, recipient of this year’s UNESCO/Guillermo

Cano World Press Freedom Prize, is currently serving a 7.5-year

sentence in Azerbaijan for her work exposing government corruption.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) says some 200 journalists like Khadija are currently jailed across the world. And prison isn’t the only way that governments co-opt or suppress the media.

Thai journalist Pravit Rojanaphruk was also invited to Helsinki, but the ruling military junta has banned him from leaving the country – a small price to be paid, he recently wrote, “as journalists elsewhere face long-term detention or even assassination.

“Most Thai journalists play it a little safe by ensuring that at least they adopt an adequate level of self-censorship when it comes to discussing or criticizing the military regime,” he told VOA. “You know when you've crossed the line [when] you get detained without charge by the military regime.”

“Only 13 percent of the world’s population enjoys a free press—that is, where coverage of political news is robust, the safety of journalists is guaranteed, state intrusion in media affairs is minimal, and the press is not subject to onerous legal or economic pressures,” the report finds.

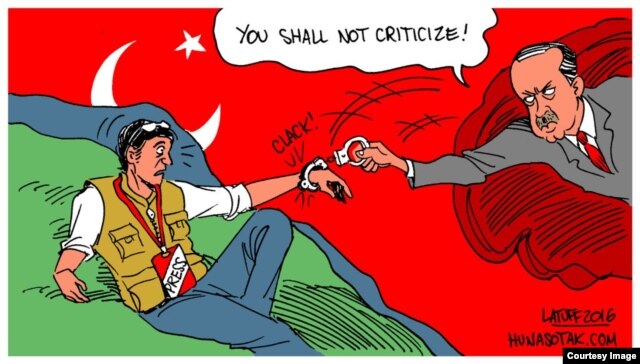

'Witch-hunt' in Turkey

Turkey witnessed a drop in press freedom over the past year as a result of a media crackdown one prominent editor called a “witch-hunt.” Reporters without Borders (RSF) ranks Turkey 151 out of 180 countries in its World Press Freedom Index, down two points since 2015.

As many as 2,000 individuals – reporters, celebrities, academics and students – are reportedly being officially investigated on charges of insulting President Recep Tayyip Erdogan or spreading “terrorist propaganda.”

Foreign journalists have come under increasing scrutiny. Der Spiegel’s correspondent was forced to leave Turkey, after the government failed to renew his press credentials. In April, Turkish police denied entry to a reporter for German State TV. Similarly, when American journalist David Lepeska returned to Ankara after a vacation in Italy, he was blocked from re-entering Turkey.

“I was told to wait in the immigration waiting area for a final decision from Ankara regarding my entry to Turkey,” Lepeska told VOA via a direct message on Twitter. “After nearly 20 hours that decision still hadn't come so, on the advice of my employers and an adviser, I decided to fly out of the country. I'm still awaiting final word from Ankara, on whether my entry ban is official and the reason for it. I can only guess that it had something to do with my reporting.”

Lepeska says he had never faced any restrictions or pressure at any time during three years’ reporting in Turkey. Nor did he ever receive any warning.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) says some 200 journalists like Khadija are currently jailed across the world. And prison isn’t the only way that governments co-opt or suppress the media.

Thai journalist Pravit Rojanaphruk was also invited to Helsinki, but the ruling military junta has banned him from leaving the country – a small price to be paid, he recently wrote, “as journalists elsewhere face long-term detention or even assassination.

“Most Thai journalists play it a little safe by ensuring that at least they adopt an adequate level of self-censorship when it comes to discussing or criticizing the military regime,” he told VOA. “You know when you've crossed the line [when] you get detained without charge by the military regime.”

Khaosod English senior staff writer Pravit Rojanaphruk during a VOA News interview in Bangkok, April 28, 2016. (Z. Aung/VOA)

Global press freedom has fallen to its lowest point in more than a

decade, notes Freedom House in its latest annual report, which scores

199 countries and territories, democracies and autocracies.“Only 13 percent of the world’s population enjoys a free press—that is, where coverage of political news is robust, the safety of journalists is guaranteed, state intrusion in media affairs is minimal, and the press is not subject to onerous legal or economic pressures,” the report finds.

'Witch-hunt' in Turkey

Turkey witnessed a drop in press freedom over the past year as a result of a media crackdown one prominent editor called a “witch-hunt.” Reporters without Borders (RSF) ranks Turkey 151 out of 180 countries in its World Press Freedom Index, down two points since 2015.

As many as 2,000 individuals – reporters, celebrities, academics and students – are reportedly being officially investigated on charges of insulting President Recep Tayyip Erdogan or spreading “terrorist propaganda.”

Foreign journalists have come under increasing scrutiny. Der Spiegel’s correspondent was forced to leave Turkey, after the government failed to renew his press credentials. In April, Turkish police denied entry to a reporter for German State TV. Similarly, when American journalist David Lepeska returned to Ankara after a vacation in Italy, he was blocked from re-entering Turkey.

“I was told to wait in the immigration waiting area for a final decision from Ankara regarding my entry to Turkey,” Lepeska told VOA via a direct message on Twitter. “After nearly 20 hours that decision still hadn't come so, on the advice of my employers and an adviser, I decided to fly out of the country. I'm still awaiting final word from Ankara, on whether my entry ban is official and the reason for it. I can only guess that it had something to do with my reporting.”

Lepeska says he had never faced any restrictions or pressure at any time during three years’ reporting in Turkey. Nor did he ever receive any warning.

No comments:

Post a Comment